Foraging societies did not have a sense of personal property and this applied to people as well as things. Groups of humans moved around with personal possessions reduced to a minimum, and no one really bothered to find out who belonged to whom. Women breastfed children regardless of who delivered them, and men helped parent them regardless of who sired them. This was normal for humans before agriculture became prevalent, before, in other words, we knew about seeds, and wombs, before the concept of paternity was part of human knowledge systems.

This argument started with Bachofen, in the late 19th-early20th century, who, in Myth, Religion and Mother Right, argued that matriarchal social organizations were prevalent throughout the Neolithic for that precise reason: that paternity was not a concept yet, and so men did not think they should know who put the seed in. Women were more revered and also more free: they had sex with multiple partners, especially in the fertile period, to make sure someone would make them pregnant.

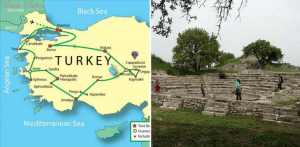

This line of thought developed further with feminist philosophers and theorists of the ‘second wave,’ including, to my knowledge, Adriana Cavarero, who, in In Spite of Plato (translated by yours truly), argues that this ignorance of paternity was a good thing, because it empowered women with sovereignty over our bodies, and the decision to be hostesses to the reproductive process necessary for the species was ours and ours alone. Two other theorists on this topic are of course Riane Eisler and Marija Gimbutas. Eisler links the social practice of competition to the social construct of paternity and the ensuing practice of controlling the female body that hosts the seed to ensue its authenticity, the fact that the resulting child is sired by the man who parents it. This, Eisler observes, not only disempowers women, but also preempts the possibility of a society organized on partnership. Because partnership requires trust and equality, and these are impossible when men’s self esteem is predicated on their ability to certify paternity. Matrifocal societies are better candidates for partnership systems. The Romans, who learned a lot from the Greeks, and the matrifocal cultures that preceded them, put this very simply: “maternity is always certain, paternity never is.” So, if it isn’t, let’s shift our focus away from it, argues Gimbutas, who studies the matrifocal cultures of the Neolithic in the pre-Indoeuropean Mediterranean, to find out that they indeed were organized around the sacred feminine, myths of fertility, the management of waters, the practice of sharing resources, including amorous, sexual,and reproductive resources, the commons, and social peace. social peace.

More to the point, this new acquaintance with polyamory as a natural, biologically-programmed, and long-standing prevalent tradition that goes back all the way to pre-history is a way to revisit the past to invent a new future. If something was done in pre-historical times we often consider it bad, backward, ‘primitive.’ But what is ‘bad’ about primitivism? What we often call ‘history’ is actually a very short period in the life of our species. A well documented one, for sure! But a ‘good’ one? The past ten thousand years have been filled with wars, empires, exterminations, genocides, tortures, competitions, extinctions and other forms of destructive behavior that we humans have inflicted on fellow creatures and a whole bunch of other species, not to mention entire habitats, climate and ecosystems, based on ever more powerful weapons and domination systems that have, ultimately, had the effect to make us, the inventor species, also a rather unhappy species, with very few individuals still able to connect with the magic of nature, the ability to contemplate existence in the present as a state of pure bliss.

Maybe those matrifocal ‘primitives’ who knew nothing about paternity, and were ‘naturally’ polyamorous because they loved nature in all its manifestations, including several people, were happier than today’s average person. So, by finding out how these poly primitives lived, by looking at the origins of sexuality in the long-standing life of our species, we can also come to a better understanding of a different time in our ‘history,’ a time when ‘history’ was actually more of a ‘herstory,’ as fellow second-wave feminists Susan Griffin and others would put it.

This will help us also dispell another myth: that women naturally ‘suffer’ polyamory while men are the ones who want it. Really? How come today’s women would ‘naturally’ demand monogamy when historically the times when polyamory was natural are times when women were revered, sovereign, and free? If paternity, the cultural construct of male insemination as ’cause’ of female fertility, is what caused dominant societies where women lost that sovereignty and that freedom, then perhaps sexual exclusivity is a result of patriarchal social organizations too?

An ecosexual future is also a Gaian future, a future when the fact that our planet Gaia is gay will finally be recognized by our sad and ingeniously destructive and self-destructive species and when we will decide to use our ingenuity to finally keep Gaia gay too.